It's 4:47 PM on Thursday. A Slack message from your engineer pops up: "What should happen if the user's connection drops during the upload?"

It’s a question about a feature you thought was buttoned up weeks ago. This isn’t just a quick clarification, it’s a symptom of a deeper problem. A vague Product Requirements Document is a tax on your team's time and focus. What you wrote was a document, a static collection of bullet points. What the team needed was a living blueprint.

A PRD isn't a conveyor belt for features, it's a switchboard that connects strategy, design, and engineering into a single, coherent circuit. When it's clear, the lights come on. When it's not, you get sparks, shorts, and blown fuses.

The Hidden Tax of a Vague PRD

Think of your PRD as a musical score. A bad score just lists the notes. It tells the orchestra what to play but offers no guidance on how. The result is a chaotic performance where every musician interprets the piece differently. Is this section supposed to be fast or slow? Loud or soft?

Nobody really knows.

A great score includes tempo, dynamics, and detailed performance notes. It gives the orchestra everything it needs to create a masterpiece. Likewise, an effective PRD doesn't just list features, it details user flows, defines edge cases, and sets crystal-clear acceptance criteria. It anticipates the questions long before they become late-afternoon Slack messages.

The Cost of Confusion

This isn't just about frustration, it carries real economic weight. This "ambiguity tax" shows up everywhere: in longer development cycles, in rampant scope creep, and in features that ultimately miss the mark. A study cited by Jama Software revealed that poorly defined requirements are a leading cause of project failure, contributing significantly to rework and budget overruns.

Every question an engineer has to ask you after kickoff is a sign of a gap in the PRD. Each one of those gaps is a tax paid in developer time, lost momentum, and team morale. A friend at a Series C company told me her team spent two weeks writing an exhaustive PRD for a checkout flow redesign. It was a beautiful document. Then an engineer asked about a legacy gift card processor.

Silence.

No one had considered it. They wrote from memory, not from a complete map of the existing flow.

The Zoom-Out Moment

Why does this happen so often? The basic gist is this: we operate in systems that reward shipping speed over deep understanding. The incentives are geared toward forward motion, not foundational clarity. The technical debt from unhandled states and foggy requirements creates a drag that slows down every single release that follows.

The goal isn't to create a document that answers every conceivable question from the future. It's to build a blueprint so clear that your team spends its energy building, not guessing.

Ground Your PRD in Reality Before Writing a Word

The best PRDs aren’t written from a blank page, they’re assembled from existing context. The most critical work happens before you type a single heading. It’s about grounding your thinking in what is, not just what could be.

Think of it like a geologist studying rock layers before deciding where to build. You don't guess where the solid ground is. You measure it. You map it. You understand the terrain completely before breaking ground on the foundation.

So, instead of describing a user flow from memory, you capture it directly from your live application. An accurate, unbiased baseline of your app's current behavior becomes your starting point. Only then can you start layering on user feedback, analytics data, and competitive analysis.

A vague or incomplete starting point inevitably leads to a misaligned team and wasted resources. It’s almost a guarantee.

From Blank Page to Actionable Blueprint

Before you write a single user story, you need to assemble your raw materials. This is the pre-writing phase that separates an adequate PRD from an exceptional one.

- Capture the As-Is Flow: Use a tool to automatically map the current user journey in your product. This isn't a wireframe, it's a factual record of what’s live right now. This becomes your canvas.

- Overlay Analytics Data: Where are users dropping off? Which steps have the highest friction? Connect your analytics to the flow map to see the story the data is telling.

- Integrate User Feedback: What are users saying in support tickets or interviews? Annotate the flow with direct quotes and pain points. Our guide on how to conduct effective primary customer research can help here.

- Validate the Core Idea: And even before that, make sure you know how to validate a business idea to ensure you're building something people actually need.

This method transforms the PRD from a creative writing exercise into an evidence-based synthesis. It grounds every decision in reality, making the final document not just a plan, but a reflection of deep understanding. Your starting point is no longer a blank page, but a rich, contextualized map of the present.

Building the Narrative Core of Your Feature

Every great feature tells a story. It has a beginning (the user’s problem), a middle (the journey they take through your product), and an end (a successful outcome). So, the real question is, does your PRD actually tell that story, or does it just list the characters?

Once you've grounded your thinking in the reality of your current product, it's time to shape that narrative. It all starts with a razor-sharp problem statement.

It’s not good enough to say, "users want to upload files." A strong problem statement is specific and framed from the user's perspective: "Users need a reliable way to upload multiple files at once without the session timing out, because they are currently forced to upload one by one, which is time-consuming and error-prone."

This precision is the foundation of a focused feature. It's the narrative hook that gets everyone aligned from day one.

The Storyboard, Not Just the Script

Think of your PRD as a film director's storyboard, not a script. A script just has dialogue. A storyboard visualizes the entire experience. It shows camera angles, character movements, transitions, and the emotional arc of the story. It communicates the how of the narrative, not just the what.

Too many PRDs are just scripts. They're walls of text describing features.

An effective PRD is a storyboard. It needs a visual anchor that maps the entire user journey, screen by screen. This visual flow becomes the single source of truth that prevents deadly misalignment. This is what I mean: instead of just writing "User uploads a file," you need to show the journey. Imagine trying to explain the intricate details of a scheduling flow, like the one explored in this Cal.com vs Calendly showdown. A text description would be pages long and riddled with misinterpretations. A visual flow map communicates the process in seconds.

Connecting the Story to Success

A story without an ending is just a collection of scenes. In product development, that ending has to be a measurable outcome. Every problem statement must be paired with a clear, quantifiable success metric. This metric answers a simple question: how will we know if we’ve won?

Without this, your team is just building toward a vague destination.

A study in the Harvard Business Review found that companies focusing on customer value metrics over internal output metrics grow 60% faster. Your success metric is the bridge between your team's work and real customer value.

Defining this metric forces clarity. It shifts the conversation from outputs to outcomes.

- Problem: The checkout flow is confusing, causing users to abandon their carts.

- Success Metric: Increase checkout completion rate from 45% to 50% within one quarter of launch.

- Problem: Recruiters spend too much time manually screening job applicants.

- Success Metric: Reduce the average time to shortlist five qualified candidates from four hours to one hour.

These metrics aren't just numbers, they are the final scene of your feature's story. They define what success looks like for the user and for the business. For instance, the research for Mercury's runway forecasting tool didn't just produce a list of requirements, it resulted in a clear PRD with UI mockups tied directly to the success of founders making better financial decisions.

Defining the Unseen Art of Edge Cases

A feature isn't defined by its happy path. It's defined by how it behaves in a storm. This is the unseen art of edge cases, the part of the PRD where a good product manager becomes a great one.

Think of an architect designing a skyscraper. They spend as much time planning for earthquakes and high winds as they do for sunny days. Why? The building’s integrity isn’t tested when the weather is calm, it’s tested when the world is shaking. Your product is no different. Your PRD is the seismic engineering report.

The truth is, the perfect user journey is a myth. Reality is messy. It’s dropped connections, invalid inputs, and users clicking things in an order you never imagined. A PRD that only accounts for the ideal path is an architectural blueprint that ignores gravity. Mapping out the component states for a simple task assignment reveals a web of complexity that text alone could never capture.

The Misaligned Economics of Shipping Features

Why do we so often neglect these critical details? The answer lies in misaligned incentives. Product managers are frequently rewarded for shipping features quickly. The celebration happens when the happy path is live.

But the long-term cost of unhandled edge cases creates a hidden tax on the organization. This debt doesn't fall on the product manager’s shoulders, it falls squarely on engineering and support.

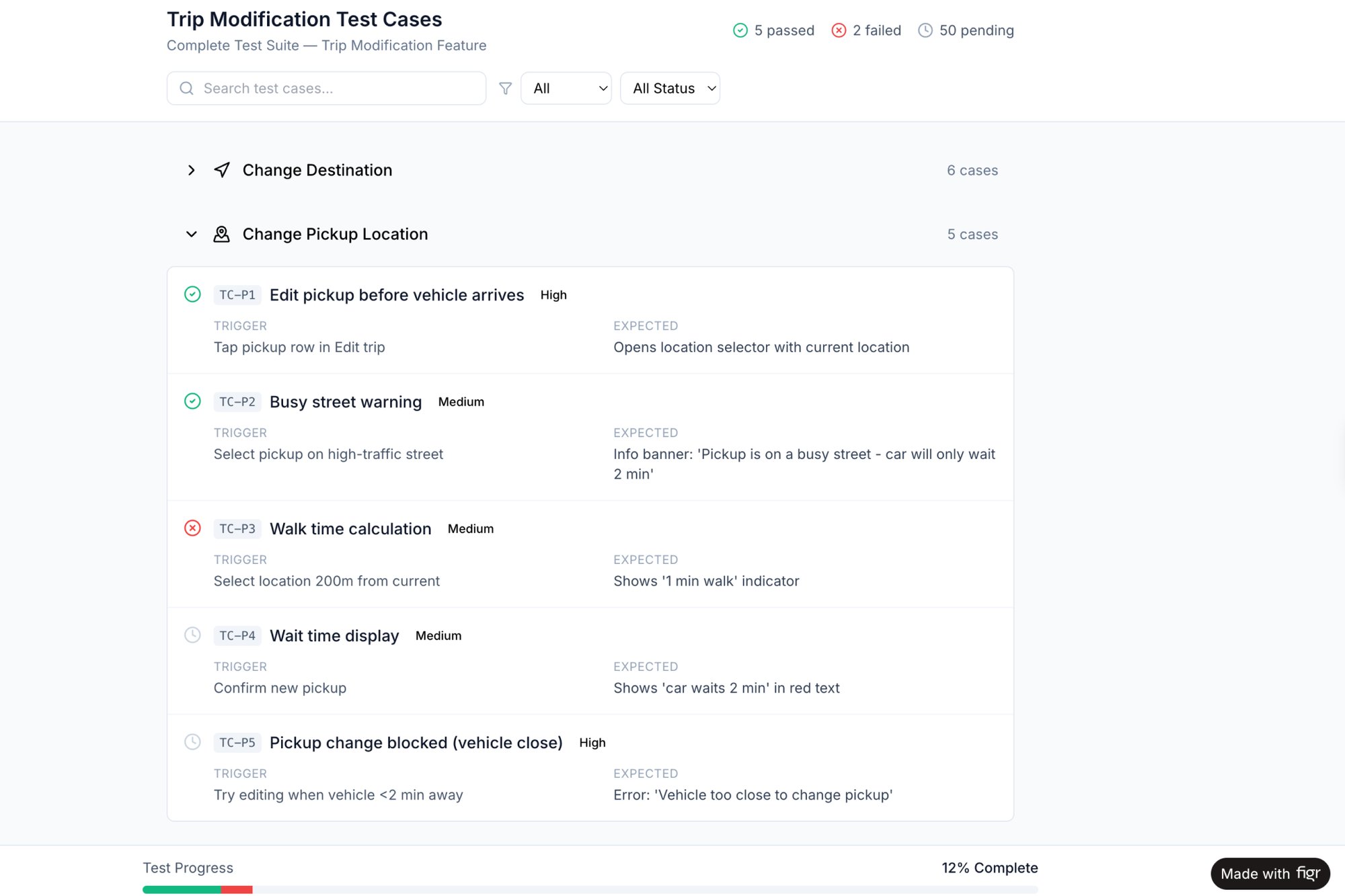

Engineers get pulled from new feature development to fix bugs that should have been anticipated. Support teams are left to manage frustrated customers who fell into a UX pothole. Exploring the potential edge cases for a Waymo trip modification is a perfect example of proactively mapping this complexity.

The real cost of a feature isn't just the initial build. It's the total cost of ownership over its lifetime, and unhandled edge cases are a high-interest loan against your team’s future velocity. You can learn more by reading about the 10 edge cases every PM misses and the outsized impact they have. They are the details that separate truly resilient products from fragile ones.

Writing Actionable Requirements and Acceptance Criteria

It’s 10:17 AM. You’ve just handed a PRD to your lead engineer. They scan it, nod, and say, “Looks good, we can build this.” That moment of clarity isn’t an accident.

It’s the result of turning abstract goals and messy user flows into instructions so precise they feel inevitable. This is where the whole thing becomes real. Your visual flows and edge case maps are the skeleton, now you need to add the muscle: the detailed requirements and acceptance criteria that tell an engineer what to build and a QA tester what to break.

Moving from Problems to Specifications

The temptation is to just start listing features. Don't. It's a trap that leads to building a solution nobody actually needs. As product leader Marty Cagan famously argues in his book Inspired, the best teams get obsessed with solving the underlying problem, not just shipping a feature list.

This principle changes how you write requirements. Think about a feature like Mercury's runway forecasting tool. The PRD didn’t start with "Build a bar chart showing monthly burn." It started with the problem: "Founders struggle to accurately forecast their cash runway, making high-stakes decisions based on pure guesswork."

The requirements flowed directly from that problem. The features were a consequence of solving the problem, not the starting point.

Using Given-When-Then for Ultimate Clarity

Acceptance criteria are your final checkpoint. They are the pass/fail tests for a user story, and one of the most effective formats for writing them is Given-When-Then.

This simple structure forces you to think through the context, the user’s action, and the expected outcome. It’s a syntax that ruthlessly eliminates ambiguity.

Let's apply it to a simple scenario:

- User Story: As a user, I want to freeze my card so I can prevent unauthorized transactions if it's lost.

- Given: I am a logged-in user viewing my card details screen.

- When: I tap the "Freeze Card" button and confirm my choice in the modal.

- Then: The card's status immediately updates to "Frozen," and I receive an email confirming the action.

This isn’t just a better way to write, it’s a better way to think. It forces you to define the initial state, the trigger, and the resulting state change with absolute precision. This process is vital for a smooth developer handoff, because it leaves nothing to chance.

When you’re trying to articulate these details, applying fundamental technical writing best practices can make a huge difference in clarity and impact. Your goal is to create a document that provides firm guardrails but gives engineering the creative freedom to find the best implementation within those constraints.

Your Next Step: Write a PRD in Minutes, Not Days

We’ve covered a lot of ground, from the high-level 'why' to the nitty-gritty 'what'. But theory is just the foundation. In product, what really moves the needle is speed and accuracy.

What if you could shrink the distance between a good idea and a well-defined spec?

The whole process we just walked through can be radically faster. The manual labor of translating thoughts into a structured document no longer has to be the bottleneck.

Think of it less like writing a novel from scratch and more like developing a photograph. The image is already there, latent in the context of your product. You just need the right tool to bring it into focus, instantly.

From Theory to Tangible Artifact

This is the part where you stop reading and start doing.

Pick one feature you're thinking about right now. It could be a small tweak or a major new initiative. But don't open a blank document. Instead, capture the existing user flow connected to that feature.

Once you have that tangible, visual map of reality, you can feed that context directly to an AI and prompt it to generate a starter PRD. A friend at a music tech startup did this for an AI-powered curation feature. Instead of blocking out a week for writing, she captured their current playlist creation flow. About ten minutes later, she had a comprehensive first-draft PRD for the Spotify AI feature.

The New Competitive Edge

The craft of writing a PRD is shifting from manual documentation to strategic direction. The new advantage is knowing how to apply your strategic thinking to a context-aware AI that handles the assembly. The bottleneck isn't your typing speed anymore. It’s the quality of your prompts and the clarity of your vision.

In short, your next step is simple. Capture a flow. Generate a draft. See for yourself how a context-aware workflow moves you from just learning to actually creating. This isn’t about replacing your thinking, it’s about amplifying it, giving you back the time to focus on the hard problems that really matter.

PRD FAQs: Straight Answers to Common Questions

Writing a good PRD feels like a balancing act. You're trying to move fast, but you can't afford to be unclear. How do you keep it from turning into a 50-page novel? How does it even fit into a modern, agile workflow?

Let's clear up a few of the most common questions.

Think of your PRD less like a contract signed in blood and more like the charter for an expedition. It sets the destination and maps the known terrain. But it has to give the team on the ground freedom to navigate the unexpected.

How Long Should a PRD Be?

This is the classic question, and the answer is always the same: as long as it needs to be to remove ambiguity, but as short as humanly possible.

Length is the wrong metric. Clarity is what matters. A crisp, five-page PRD with sharp user flows and airtight acceptance criteria is infinitely more valuable than a meandering 20-page document filled with vague ideas.

A single, well-constructed user flow diagram can often replace pages of dense text.

PRDs vs. User Stories: What's the Difference?

It’s simple: the PRD is the container, and user stories are the contents.

The PRD provides the big-picture context. It’s the "why" and the high-level "what." It answers critical questions like:

- What problem are we actually solving?

- What are the business goals?

- Who are we building this for?

- How will we know if we’ve succeeded?

User stories are the granular requirements that live inside that container. They break the feature down into small, testable chunks from the user's perspective. Think: "As a user, I want to filter my dashboard by date range so I can see my performance over time."

Should a PRD Include UI and UX Designs?

Yes and no. The PRD’s job is to define the problem and the requirements, not to dictate the final pixels.

It should absolutely include low-fidelity wireframes or user flow maps. These are essential for giving the team context on how a user will actually move through the feature. Without them, you’re just describing things in a vacuum.

But high-fidelity, pixel-perfect mockups? Those should be linked from the PRD, not embedded within it. This separation is key. It allows the design to evolve based on feedback and technical constraints without forcing you to constantly update the core requirements doc.

Your PRD is the bridge between a good idea and a great product. With Figr, you can stop staring at a blank page and start with a complete, context-aware draft in minutes. Capture any user flow, and let our AI agent generate the PRD, edge cases, and user stories for you.

Start building with clarity at https://figr.design.