It's 4:47 PM on Thursday. Your VP just asked for something visual to anchor tomorrow's board discussion. You have a PRD. You have bullet points. You have 16 hours and no designer availability. In that moment of pressure, the team defaults to what feels safe: a long list of features for the "MVP."

This is the moment most teams get the entire concept wrong. They've fallen for a dangerous myth.

The myth is that an agile minimum viable product is a smaller version of a final product. It’s not. It’s a scientific instrument, designed to answer one question with brutal efficiency. Its goal is not completion; it's validated learning.

The Myth Of The Complete MVP

We've been trained to see products as checklists. The more boxes we tick, the more "complete" it feels. But an agile MVP isn't a feature checklist. It’s a laser-focused experiment designed for a single purpose: to test a make-or-break assumption with the least possible investment.

A Scientific Instrument, Not A Scaled-Down Product

Picture your product vision as a distant star. An MVP isn’t a smaller, slower spaceship meant to eventually get there. It’s a telescope pointed in that star's direction. Its only job is to bring back one clear piece of data: are we even looking at the right star? Is there anything there at all?

Last week I watched a PM present an MVP roadmap with 47 user stories. The team was proud. But when I asked what single question this massive release would answer, the room went quiet. They confused activity with progress.

Shipping features feels productive. Learning what customers actually value is productive.

The basic gist is this:

- A scaled-down product tries to serve many needs poorly.

- An agile MVP tries to solve one core problem exceptionally well, just to see if anyone cares.

This distinction is everything. A team building a task management app might be tempted to add calendars and team collaboration. The instrument-minded team builds only the ability to create and complete one single task, then measures if people come back to do it again. The first approach delivers a weak product. The second returns a clear signal.

The Incentives Driving Feature Creep

Why do we cling to the fantasy of a "complete" MVP? The incentives are powerful. Shipping a bare-bones experiment feels nakedly risky. It exposes our core assumption to immediate judgment.

According to a Harvard Business Review article, roughly 80% of companies now use some form of Agile. Yet many still struggle with the core principle of shipping to learn, not just to ship.

Adding more features feels safer. It’s a buffer. If the MVP fails, we can blame the missing features instead of confronting our flawed assumption. It’s a form of corporate hedging that just delays the truth. This is a zoom-out moment: the economic pressure to "show progress" often translates into a long feature list, even when that list is taking you in the completely wrong direction.

Breaking this cycle means reframing the goal. The purpose of an agile minimum viable product isn't to build a successful product on the first try. It’s to find the fastest, cheapest path to a difficult truth. You can learn more by conducting effective primary customer research to inform your MVP strategy.

The next step is to stop asking, "What features should our MVP have?"

Instead, ask this: What is our single most important hypothesis, and what is the absolute cheapest way to test it?

Crafting A Falsifiable Product Hypothesis

Your MVP is an instrument, but what is it measuring? Before you design a flow or write a story, you need a clear, falsifiable hypothesis. It’s the compass for your experiment.

A map gives you a detailed route, assuming the destination is correct. A compass just gives you a direction: True North, letting you navigate an unknown landscape and adjust as you learn. Most teams build maps for territories that don't exist yet.

A good hypothesis isn't a vague goal. It’s a sharp, testable statement about the future.

This is what I mean: a powerful hypothesis has three parts.

The Structure of a Testable Hypothesis

The most effective structure is deceptively simple, but it forces clarity where ambiguity hides. It moves you from wishful thinking to a specific, measurable belief that your MVP can actually test.

Here’s the framework:

We believe that by building [THIS CAPABILITY] for [THIS AUDIENCE], we will achieve [THIS MEASURABLE OUTCOME].

This structure isn’t just a template; it’s a filter. If you can’t fill in each blank with precision, you don’t have a clear idea yet. You have a hunch.

Let’s see it in action. A team might start with a vague goal like "increase user engagement." What does that even mean? Using the framework forces specificity.

- Vague Goal: Increase user engagement.

- Sharp Hypothesis: We believe that by creating an AI-powered project brief generator for freelance marketers, we will increase project completion rates by 15% within 60 days.

The difference is night and day. The second version names the feature, the target user, and the specific success metric. You can prove it or, more importantly, disprove it. This is the essence of a falsifiable hypothesis. As physicist Richard Feynman noted, "It doesn't matter how beautiful your theory is... If it doesn’t agree with experiment, it’s wrong."

From Broad Idea To Sharp Instrument

Last year, a product manager at a B2B SaaS company wanted to improve their onboarding. Her initial goal was "make it easier for new users to get started." It’s a noble goal but impossible to measure directly.

We spent an hour breaking it down. Who was struggling the most? What was the first critical action a user needed to take to see value?

This led to a much sharper hypothesis:

"We believe that by creating an interactive setup checklist for newly onboarded account administrators, we will reduce support tickets related to initial configuration by 40% in their first week."

Now they had a real experiment to run. The MVP wasn't a "new onboarding flow." It was a simple, focused checklist component. For teams looking to build this kind of focused experiment, understanding how to validate a B2B startup idea provides a crucial foundation for testing these core assumptions effectively.

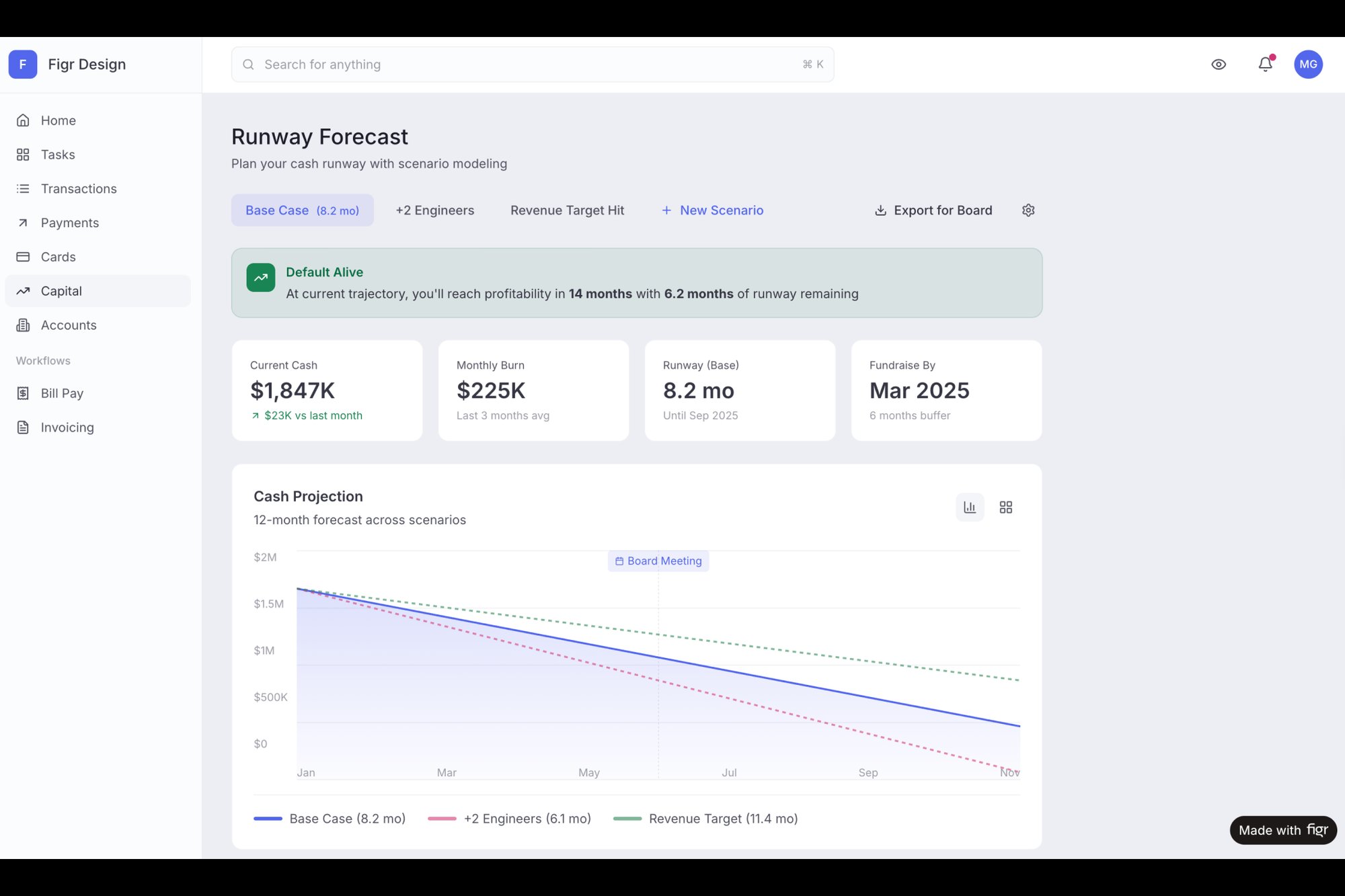

You can see how this thinking applies to even small features. A team might want to test if adding an AI reply feature improves email productivity. They can build a high-fidelity prototype like this AI-powered Gmail reply to gather feedback before committing to a full build. Or, when considering a new feature like runway forecasting, a PRD can outline the entire hypothesis and success metrics, as seen in this Mercury forecasting PRD.

A hypothesis is a bet. Your MVP is how you place that bet with the smallest amount of chips possible to see the outcome.

In short, a well-crafted hypothesis is your most important product spec. It defines the "why" before you get lost in the "what" and "how." You can learn more about how this connects to the broader product strategy in our guide on how to validate features before writing a single line of code.

Your next step is to take your biggest idea and force it through this structure. Is it specific? Is it measurable? Is it tied to a core business assumption you absolutely cannot afford to be wrong about? If not, keep refining. This discipline is what separates teams that build useful things from those that just stay busy.

Designing The Minimum Viable Experiment

A sharp hypothesis is a destination. How do you design the vehicle that gets you there? This is the moment you translate an abstract belief into something a real user can touch.

Most teams think in terms of a layer cake, building a thin, brittle slice of every single layer: a little UI, a little backend, a little reporting. The result is a fragile experience that tests nothing of substance.

An agile minimum viable product is not a layer cake. It’s a core sample.

Think of a geologist drilling into the earth. They don’t scrape a thin layer off the top. They drive a narrow cylinder deep into the ground to extract a complete, vertical cross-section. That sample reveals the composition of every layer in one specific spot. Your MVP should do the same for your user experience.

Mapping The Critical User Journey

This means your first step isn’t to list features. It's to map the single most important path a user must take to validate your hypothesis. What is the one job they need to accomplish that proves you're onto something?

For a fintech startup, the hypothesis was that founders needed a better way to forecast their financial runway. Instead of building a full dashboard, we focused on the core sample: the journey of inputting current cash, adding monthly burn, and seeing a projected "zero cash" date. That was it.

Visualizing the most critical steps in a journey is a powerful way to define scope. A great user flow map, like this one for a Shopify checkout setup redesign, can make the boundaries of your experiment crystal clear for everyone. It defines what’s in and, just as importantly, what’s out.

As you can see, the user journey you map must directly connect the capability you’re building to the specific outcome you need to measure for a defined audience.

Prototyping The Feeling Of Real

Once your journey is mapped, the goal is to create an experience that feels real enough to gather genuine feedback. A wireframe can test a layout, but a realistic prototype tests a reaction.

A friend at a Series C company needed to validate that a new runway forecasting tool would be used by busy founders. Instead of spending two months building it, his team used Figr to build a high-fidelity prototype of just the core calculation and sharing flow. You can see how this was framed in their runway forecasting PRD.

They put it in front of ten target users and learned within a week that the core concept was sound, but the way they presented the data was confusing. That’s a two-month engineering mistake avoided in five days. This is the economic power of prototyping, a topic we explore in our guide on the best practices for prototyping in agile development.

Defining Done With Acceptance Criteria

The final piece is translating your user flow into clear instructions for engineering. This is where acceptance criteria come in. They are the "definition of done" for your MVP.

Instead of vague user stories, you can generate specific, testable conditions. What happens when a user enters a negative number? What does the error state look like?

For a feature that allows a user to freeze their bank card, the happy path is simple. But the real work is in the edge cases. By exploring every possible state, you can generate a complete set of test cases, like these ones for a Wise card-freeze flow. This gives engineering a precise blueprint, eliminating the ambiguity that kills momentum.

Your next step is to take your hypothesis and map the single user journey that tests it. Don't build the whole house. Just build one perfect, load-bearing wall and see if it stands.

Launching To Learn, Not Just To Ship

Shipping your agile MVP isn’t the finish line. It's the starting gun. The moment the code goes live is the quietest part of the process, the beat of silence right before the real noise of data starts pouring in.

An MVP without metrics is just a guess pushed to production.

Time isn't a conveyor belt; it's a switchboard. Launching to learn means you design the experiment with the same discipline you used to design the product.

Finding Your North Star Metric

To run a clean experiment, you need to isolate one variable. For your MVP, that variable is your North Star metric. This isn't just another KPI; it's the one data point that directly validates or invalidates your core hypothesis. Everything else is just noise.

What makes a good North Star metric? It’s specific. It’s tied directly to user behavior. And it reflects the value you deliver, not just activity.

A friend at a productivity startup once walked me through their dashboard. Daily active users? Up. Sign-ups? Climbing. But their hypothesis was that a new collaboration feature would make teams stickier. When we dug in, we found that less than 10% of teams who tried the new feature ever used it a second time. Their shiny new feature had a staggering 90% drop-off after the first use.

They were tracking the wrong star.

Here's the difference:

- Vanity Metric: Total sign-ups or downloads.

- Actionable Metric: The percentage of new users who complete the core action within their first session.

- Vanity Metric: Daily active users.

- Actionable Metric: Week-two retention of users who engaged with the new feature.

The right metric becomes a filter for every product decision. Does this change move our North Star? If the answer is no, why are we even talking about it?

Instrumenting The Feedback Loop

Once you have your metric, you need to blend the quantitative with the qualitative. Your MVP needs both a telescope and a microscope.

Quantitative Data (The Telescope): This is your analytics setup. It tells you what users are doing at scale. You absolutely must instrument every single step of your critical user journey.

Qualitative Insights (The Microscope): This is you, talking to actual human beings. Analytics might show you a 70% drop-off at the payment screen. An interview will tell you it’s because they were confused by the pricing tiers. The numbers tell you what; the conversations tell you why.

An agile minimum viable product is an engine for generating customer feedback. The goal of the launch isn't to get applause; it's to get data that fuels the next cycle of the build-measure-learn loop.

A complete feedback loop needs both. Without analytics, your interviews are just anecdotes. Without interviews, your data has no context. Setting up this loop is a core part of the MVP development process, a topic we explore in our guide to A/B testing best practices.

Your next step isn't to plan the next dozen features. It's to choose your North Star metric and set up the instrumentation to track it from the very second your MVP goes live. Don't just ship your product.

Launch your experiment.

Pivot Or Persevere: The Moment Of Truth

The data is in. The frantic energy of the launch has been replaced by the quiet hum of analytics. This is the moment where the experiment ends and the real decision-making begins.

It’s never a clean yes or no. The data doesn’t show up with a neat label. It’s a messy stream of signals that you and your team have to interpret. So, what now?

Your most critical choice is whether to pivot or persevere. This isn't about winning or losing; it's about learning and moving forward with clarity. Think of it like a sailor navigating by the stars. The goal isn't just to keep sailing, it's to adjust your course based on your readings to actually reach your destination.

Interpreting The Spectrum Of Outcomes

The results from your agile MVP will almost never be a simple pass or fail. They exist on a spectrum. The key is to get good at categorizing the signals you're receiving.

Here are the four most common signal types:

- Strong Validation: Your North Star metric blew past your target. Qualitative feedback is glowing. The core assumption holds.

- Soft Validation: The metrics are heading in the right direction but didn't hit your target. The signal is promising, but noisy.

- Ambiguous Signals: The data is flat or contradictory. A small, vocal group loves the feature, but the vast majority is indifferent.

- Clear Invalidation: The metrics are flat or negative. Users aren't touching the feature. Your core assumption was wrong.

Each of these outcomes demands a different response. Strong validation means you persevere. Soft validation suggests a pivot is needed. Ambiguous signals? They demand a new experiment. And clear invalidation? That’s a successful experiment, too. It’s a signal to stop before wasting more resources.

The Economics Of Pivoting

Let's zoom out. Organizations aren't purely rational. The sunk cost fallacy is a powerful gravitational force. "We've already spent three months on this" is one of the most expensive sentences in business.

True courage isn’t shipping more features for a failing product. It’s having the discipline to pivot or stop. In his foundational book The Lean Startup, Eric Ries frames this as the soul of the build-measure-learn loop. The learning, not the building, is what creates value.

This is why the methodology boasts a 64% success rate compared to the Waterfall model's 49%. It reduces the risk of building something nobody wants, a fate that befalls 42% of startups who fail due to a lack of market need. To navigate these complexities, understanding various strategic decision making frameworks can provide valuable structure for critical choices.

A pivot is not an admission of failure. It is an acknowledgment of new, hard-won knowledge. It's a strategic course correction, not a surrender.

Your next move is to create an unemotional process for this decision. Before your next launch, agree with your team on what each outcome on the spectrum will mean. Define the specific metric thresholds that will trigger a pivot, persevere, or kill decision.

Make the choice before the data makes you emotional.

Let's Talk Through Some Common MVP Hurdles

Even with the best playbook, questions pop up when theory meets reality. The whole point of an agile MVP is to trade the false comfort of a massive feature list for the ambiguity of a focused experiment. It’s a different way of thinking.

Let's unpack the questions I hear most often from teams on the ground.

How “Minimal” Is Minimal, Really?

Think of your MVP as a single key, not a master key. Its only job is to unlock one door: the one that validates your most critical hypothesis. The right measure isn't the number of features, but the amount of learning you get for the effort you put in.

Here’s a simple filter: if a feature doesn't directly help you prove or disprove your core assumption, it’s out. It’s just noise. For an MVP, minimalism isn't about being lazy; it's a form of scientific rigor.

Isn't a Prototype Just an MVP?

This is a big one. A prototype tests usability. It answers the question, "Can people use this thing?" An MVP, on the other hand, tests viability. It answers the much more important question, "Will people use this thing?"

A high-fidelity prototype can be part of your MVP strategy. You might build one to test a complex flow, like these component states for a task assignment, to get early feedback. But the MVP itself has to deliver a sliver of real, functional value to see if your core idea has legs.

What Do We Do With Negative Feedback?

Negative feedback isn't a failure; it's a gift. It's the data that tells you your hypothesis was wrong, potentially saving you years of building something nobody wants. Remember, the goal of an agile minimum viable product isn't to get a standing ovation. It's to get clear, honest feedback.

The economic landscape has shifted. Today, something like 80% of product managers work in Agile shops. Why? Because while the cost to build software is plummeting, user attention has never been more scarce. This is why teams using MVPs are twice as likely to hit their goals: they learn faster. You can dig deeper into product development frameworks on pragmaticcoders.com.

When that tough feedback rolls in, your job is simple: dig in. Unpack the "why" behind it. Use that insight to pivot your approach or to make the courageous call to stop.

At Figr, we built our AI design agent specifically to shorten this loop. It takes your high-level goals and translates them into testable artifacts you need: user flows, prototypes, and even edge cases, in minutes, not weeks. Instead of starting with a blank canvas, you start with a well-structured experiment. Design confidently and ship faster with Figr.