It's 4:47 PM on Thursday. Your VP just asked for something visual to anchor tomorrow's board discussion. You have a PRD. You have bullet points. You have 16 hours and no designer availability. You promised a full suite of features months ago, but customer conversations have pulled you in a different direction.

That roadmap you proudly presented now feels like a historical document.

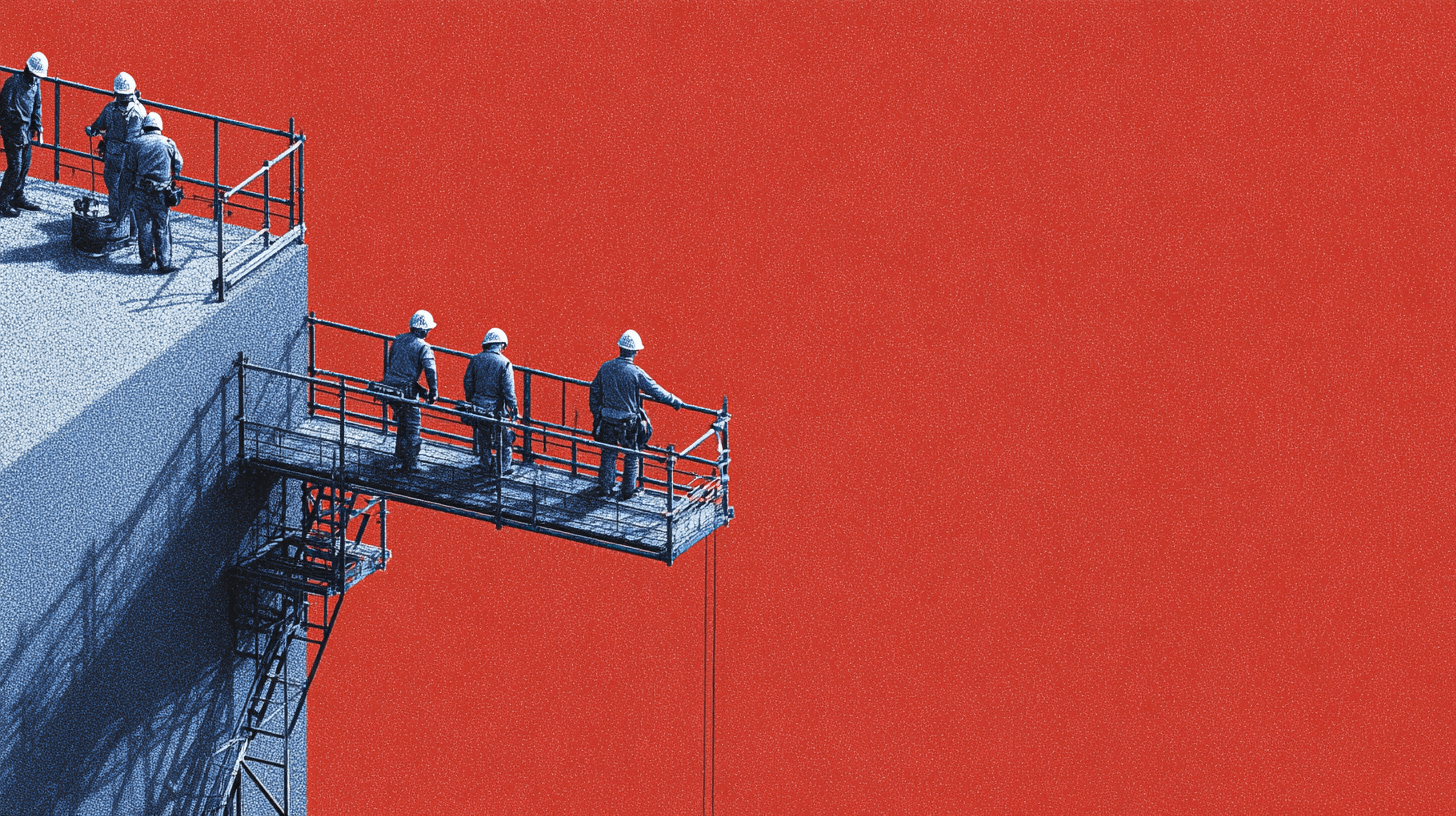

This is the exact moment most product teams feel trapped. Chained to a plan that stopped making sense weeks ago, they keep building features for a future they’re no longer sure is coming. This is what happens when you treat software development like construction, where a fixed blueprint precedes any work. But software isn't a building.

It's a conversation.

The mvp agile development process is designed to dismantle this myth of the long-term, predictive roadmap. The goal isn't to build less. It's to learn faster with less.

Moving Beyond the Monolithic Roadmap

The MVP as a Scientific Probe

We need to completely reframe what a Minimum Viable Product is. Is it just a cheap first version or a buggy beta? No. Think of an MVP as a scientific instrument: a probe you send to an unexplored planet.

Its only job is to send back data.

This probe isn't meant to be a permanent colony. It isn't designed for comfort or long-term living. It’s built to answer one critical question about the environment: Is there oxygen? Is the ground stable? Does this market actually behave the way our hypotheses predict?

This is what I mean: every feature, every line of code, and every design choice must serve the single, focused purpose of gathering specific, actionable data.

The purpose of an MVP is to test a fundamental business hypothesis. It is an exercise in reducing risk, not just an exercise in reducing scope.

Last week I watched a PM at a fintech startup defend a three-month MVP plan. When I pressed him, he admitted that only two weeks of work were needed to test their core, riskiest assumption. The other ten weeks? That was for polish, edge cases, and "nice-to-haves" that stakeholders had requested. His MVP was just a miniature version of the final product, not a tool for learning.

His plan wasn't designed to answer a question. It was designed to deliver a small promise.

De-Risking Your Product Strategy

This shift in thinking is the first, and most crucial, step in de-risking your entire product strategy. Instead of placing one large, expensive bet on a fully-formed idea, you place a series of small, inexpensive ones.

- Financial Risk: You stop yourself from investing heavily in features nobody actually wants.

- Market Risk: You confirm a real problem exists before you build the complete solution for it.

- Technical Risk: You can test the feasibility of your core technology with a very limited implementation.

The monolithic roadmap assumes time is a conveyor belt, moving predictably from one milestone to the next. But building a product is more like navigating a switchboard, constantly rerouting based on new information. MVP agile development gives you the control to make those connections deliberately. Mastering the art of choosing the right tools is key here, and it's worth exploring the differences between various product roadmap and design tools to support this flexible approach.

The grounded takeaway is this: before your next planning meeting, identify the single most dangerous assumption in your plan. Then, ask your team, "What is the absolute smallest thing we can build to prove or disprove it?"

That’s your real MVP.

How to Define Your Core Learning Goal

Before a single user story gets written, before a wireframe is sketched, before you even book the kickoff meeting, you have to answer one question.

What is the single, most important thing we need to learn?

This isn't a trick question. It’s the very foundation of the MVP process, yet it’s the step most teams skip. They get excited and jump straight into solutions, debating features and cramming the backlog with tasks. What they end up building is a collection of answers to questions nobody was asking.

Most MVPs fail because they’re designed to be miniature versions of a final product, not sharp instruments for discovery. They try to answer too many questions at once: is it about user acquisition? Technical feasibility? Price sensitivity? The result is a muddled offering that excels at nothing and validates even less.

A friend at a B2B SaaS company told me they spent six months building an "MVP" that was really just a bucket for every stakeholder's pet feature. It launched to crickets. Why? Because it answered no single, burning question for any specific user. It was a solution desperately searching for a problem.

From Vague Ideas to Falsifiable Hypotheses

Your job is to sharpen your team's focus from a vague business goal into a single, testable hypothesis.

A weak goal sounds like, "We want to build a tool for social media managers."

A strong learning goal sounds like, "Will social media managers trade their email address for a report that analyzes their competitor's posting frequency?"

One is an ambition. The other is an experiment.

The basic gist is this: a real MVP learning goal has to be falsifiable. You have to be able to fail. If you can’t fail, you can’t learn.

This isn’t just theory; it's backed by how successful teams operate. The iterative nature of Agile, built around these exact learning loops, is why it has such a high success rate. Teams using Agile hit peak project performance at 39% over other methods, mostly because short sprints force them to get real feedback and pivot without burning months on unproven ideas. You can dig into more data in the full State of Agile Report.

Using Assumption Mapping to Find Your Focus

So how do you find that one critical question? You map your assumptions.

Think of your product idea as a constellation of beliefs. Some are solid, known facts. Others are faint, distant guesses. Your riskiest assumption is the star that, if it disappears, causes the entire constellation to collapse. That's the one you test first.

An MVP is not a product. It's a question you ask your market. The features are just the syntax of that question.

To find it, get your team in a room and ask:

- What must be true for this product to succeed? List every single belief, from user behavior to market size to technical capabilities.

- How certain are we about each of these beliefs? Rate them on a scale from "we have hard data" to "this is a complete guess."

- What’s the impact if we’re wrong? Rate the damage from "minor setback" to "company-ending."

Your core learning goal lives in that top-right quadrant: high uncertainty and high impact. This is your riskiest assumption, and it should be the sole focus of your MVP.

To get really structured with this, an AI strategy prioritization framework for MVPs can help you navigate these critical decisions. You can also learn how to validate features before committing any development resources.

Your MVP's goal is not to ship code. It is to buy information at the lowest possible cost. Frame your primary objective as a clear, falsifiable hypothesis, and you’ll build a product that learns its way to success.

Defining the Critical Path: Your MVP Backlog

You've nailed down your core question. It’s sharp, focused, and ready to slice through the noise. Now, how do you translate that single, burning question into a product backlog? What’s the very first thing a user actually does?

This is the exact point where most product teams go off the rails. They open Jira, start listing features, and create tickets for "user login," "dashboard," and "profile settings." This isn't mapping a journey; it's just making a to-do list.

In agile MVP development, your backlog isn't a collection of features.

It's a story.

The goal is to map out the absolute shortest path a user can take to get an answer to your hypothesis. Nothing more, nothing less.

The Trunk and Branches Analogy

Picture your product idea as a massive tree. It has countless branches, each representing a potential feature, a niche use case, or a secondary user segment. The common mistake is trying to build a little bit of every branch, hoping the result is a well-rounded tree right from the start.

That approach is a recipe for disaster. It creates a weak, spindly product that can’t support its own weight and delivers no real value to anyone.

Instead, your MVP needs to be the trunk of the tree and nothing else.

The trunk represents the single, critical path your very first user must walk to experience that "magic moment": the point where they get the core value you promised. It is the straightest possible line from their problem to your solution.

Every other idea, no matter how brilliant, is a branch. Password resets? That's a branch. Social sharing features? A branch. A fancy admin panel? Definitely a branch. You can explore those later, but only after you’ve proven the trunk is strong enough to stand on its own.

The rule is simple: every user story in your initial backlog must directly serve that critical path. Anything else is waste.

Visualizing the Critical Path

A friend of mine, a PM at a Series C company, once told me about their first MVP. They spent four months building a complex platform for event managers, packed with features. After launch, they discovered their target users didn't need a "platform" at all. They just needed a faster way to create a guest list from a spreadsheet.

The team had built a dozen beautiful branches before they even knew if the trunk was planted in fertile soil.

To avoid that fate, you build a user story map. It’s a deceptively simple but powerful way to visualize the user’s journey.

- Identify the User: Who is the one person you are building this for? Get ruthlessly specific. Not "marketers," but "Sarah, a content marketer at a 50-person startup."

- Define the Goal: What is the single outcome Sarah needs to achieve that proves or disproves your core hypothesis? For example, "Sarah needs to generate a list of 10 relevant content ideas in under five minutes."

- Map the Narrative Steps: What are the major activities she must perform in sequence? This becomes the backbone of your map: the trunk. It might look something like this:

Connect Data Source→Define Topic→Generate Ideas→Export List. - Detail the Stories: Under each of those big steps, list the specific user stories needed to make it happen. For instance,

Connect Data Sourcewould include a story like, "As Sarah, I can authenticate my Google Analytics account."

This forces you to think in a straight line. It makes it painfully obvious when a proposed feature serves the core journey versus when it's just a distracting branch. If you want to go deeper on this, check out this excellent guide on what a user journey map is and how to build one.

The Economics of Simplicity

Let's zoom out for a second. The economics of software development punish complexity at an exponential rate. Every feature you add doesn't just come with its own development cost; it adds a hidden tax on everything else.

A single, linear path dramatically reduces hidden costs from edge cases, QA cycles, and the cognitive load on both your team and your users. This disciplined focus is your greatest economic advantage.

More code means more bugs. More UI elements mean more for users to learn. More options mean more decision fatigue. By focusing only on the trunk, you aren't just deferring features: you are actively buying yourself speed and clarity.

So, before you write a single ticket, physically map out that user journey. Turn your core question into a simple, linear narrative. If a feature doesn't fit directly into that sequence, it doesn't belong in your MVP.

Prioritization Matrix From Idea to Sprint One

To get even more tactical, you can use a simple matrix to force hard decisions. This framework helps you move from a big cloud of ideas to a focused Sprint One backlog by scoring each feature against your core hypothesis.

Feature IdeaCore Hypothesis Impact (1-5)Effort (1-5)Decision (Build, Defer, Discard)Google Analytics Auth52BuildManual CSV Upload42BuildGenerate 10 Content Ideas54BuildExport Ideas to CSV51Build"Save for Later" Function22DeferUser Profile Settings13DiscardSocial Sharing Buttons11Discard

This exercise isn't about being perfect; it's about being honest. If a feature scores a 1 or 2 on "Core Hypothesis Impact," it has no business being in your MVP, no matter how low the effort. Your goal is to find the high-impact, low-to-medium-effort items that form that critical path. That's your trunk. Everything else can wait.

Structuring Your Two-Week Learning Loop

An Agile sprint for an MVP is not a feature factory. It's a dedicated learning cycle. Too many teams adopt the ceremonies of Agile—daily standups, two-week sprints—but completely miss the point. They just use the structure to churn out code, measuring success by the number of tickets they close.

This is a critical mistake.

The goal isn't just to build the thing right; it's to build the right thing. And you only discover what’s "right" by asking better questions. Because of this, every sprint must be structured around answering a single, specific question. This reframes the entire process from one of production to one of investigation.

From a Shipping Goal to a Learning Goal

Let’s make this concrete. A typical, feature-focused sprint goal sounds something like this: "Ship the user dashboard." It's an instruction. It tells the team what to build.

A learning-focused sprint goal is entirely different: "Validate if users understand our core metric on the dashboard."

Can you feel the shift? This isn’t a small change in wording. It’s a fundamental change in mission that cascades through every single role on the team.

- UX designers no longer just create a visually appealing layout. Their primary job is now designing an experiment to test for comprehension. They’ll likely create a few variations and lean heavily on user feedback mechanisms.

- Engineers don’t just build a front-end and connect it to an API. They build for instrumentation first, making sure every click and hover related to that core metric is tracked. Those analytics hooks aren't an afterthought; they're as critical as the login button.

- QA professionals shift their focus from just finding bugs. Their success criteria now include answering, "Does the completed work allow us to confidently answer our learning goal?" They’ll write test cases that validate the data collection just as much as the feature’s functionality.

This visual shows the flow from defining that core learning question to creating a focused MVP backlog for your sprint.

The key insight here is that a clear, focused question acts as a powerful filter. It ensures every piece of work directly contributes to learning.

A Sprint That Feels Like a Science Fair

When you orient your sprint around a learning goal, the daily rituals change their texture.

Day 1 Sprint Planning: The main event isn't story point estimation. It's a focused session where the Product Manager presents the core question for the next two weeks. The team’s job is to break that question down into the smallest possible set of tasks required to get a reliable answer.

Daily Standups: The classic "What did you do yesterday?" becomes less relevant. The new focus is, "What are the current blockers to our learning?" An engineer might be blocked not by a technical issue, but by a missing analytics event. A designer might need clarity on which user segment to test with first.

Sprint Review: This is where the most important transformation happens. The sprint review ceases to be a demo where engineers show off completed features.

It becomes a science fair.

Your sprint review isn't a performance for stakeholders. It's a presentation of experimental findings, where the team shares the hypothesis, the data collected, and the conclusion.

The team presents the original learning goal, shows the piece of the product they built to test it, and then presents the data. What did users do? What feedback did they give? Did we validate or invalidate our assumption? This approach creates a culture of intellectual honesty. You can learn more about how this connects with the actual build phase by reading our guide on best practices for prototyping in agile environments.

The outcome of this review isn't just a round of applause. It’s a clear decision about what to learn next. This cycle of question, build, measure, and conclude is the true engine of MVP agile development. It turns your product team into a rapid learning machine, not just a feature factory.

How to Measure What Truly Matters

The MVP is live. The deployment script ran clean. You take a breath.

And then, almost immediately, someone in the room asks the wrong question: "So, how many sign-ups do we have?"

This is the moment that separates a disciplined team from an undisciplined one. Success, at this fragile stage, isn’t about page views or user counts. Those are vanity metrics: empty calories for the ego. They tell you people showed up, but not if they cared, or if you solved their problem.

In short, success is measured by the clarity of the answer you get to your core question.

The Validation Dashboard

The only way to stay focused is to build your instrument panel before you launch. This isn't your sprawling business intelligence dashboard with a dozen charts. It's a lean, temporary Validation Dashboard holding just three to five key metrics that directly test your sprint’s learning goal.

Think of it this way: if your core hypothesis is about user engagement, your dashboard should feature metrics like daily active use or retention cohorts. A cumulative user count is just noise at this point.

The goal is to get a signal, not to make a splash.

A Validation Dashboard acts as a compass, not a speedometer. It tells you if you're headed in the right direction, not just how fast you're moving.

This approach also forces a critical conversation about the two types of data you absolutely need to make a sound judgment.

Balancing the What and the Why

Your Validation Dashboard needs to tell the whole story, and that means measuring both behavior and motivation. You need the what and the why.

- Quantitative Data (The What): These are the hard numbers. They tell you exactly what users did. Think percentage of users completing a critical path, average time on a key screen, or the drop-off rate at a specific step.

- Qualitative Feedback (The Why): This is the context behind the numbers. It tells you why users did what they did. This comes from user session recordings, quick in-app surveys, or direct interviews.

A common failure is relying exclusively on one or the other. If 70% of users abandon the payment screen (quantitative), you know you have a problem. But only a user interview (qualitative) will tell you if it's because of a confusing form field or a fundamental lack of trust in your brand.

Defining Your Thresholds Before You Launch

The hardest part of measurement is interpretation. How do you know if the numbers are good enough? You have to draw a line in the sand before the first user ever sees your product.

Before you launch, your team must agree on clear "pivot or persevere" thresholds. These are predetermined success criteria that strip emotion and sunk cost fallacy from the decision-making process.

For example:

- Persevere: "We will continue with this approach if at least 15% of new users complete the core workflow within their first session."

- Pivot: "If fewer than 5% of users complete the core workflow, we will pause new feature development and conduct five 'why' interviews to understand the core friction."

This proactive framework turns an MVP from a simple launch into a true experiment. It’s the defining characteristic of a mature mvp agile development practice. By creating these thresholds, you commit to acting on the data you get back, ensuring every cycle leads to genuine learning, not just more code.

The Most Important Meeting: Pivot, Persevere, or Park

Your first learning loop is complete. The experiment ran, the first wave of data is trickling in, and your Validation Dashboard is blinking with fresh numbers. For a second, it feels like you've reached the finish line.

You haven't. This is the starting gate for the most critical decision in the entire MVP agile development process.

This is where discipline has to trump emotion. So many teams stumble right here. They either declare a premature victory based on a few shiny vanity metrics or fall into analysis paralysis, endlessly debating what the numbers really mean. The point isn't just to build the next thing; it's to make a calculated choice.

That choice is simple: do you pivot, persevere, or park?

https://www.youtube.com/embed/8pNxKXSUGE

Reading the Conflicting Signals

What happens when the data tells two completely different stories? A friend of mine at a health-tech startup ran into this exact wall. Their quantitative data looked fantastic: 75% of trial users successfully completed the core workflow. On paper, it was a home run.

But the qualitative feedback? Absolutely brutal. Users called the interface “clunky” and “confusing.” They muscled through the task, but they hated every second of it.

This is where a product manager earns their keep. His team didn't just pop the champagne over the high completion rate. They synthesized the conflicting signals.

- What it meant: The problem they were solving was real. It was painful enough that users were willing to fight a terrible user experience to solve it. This was a massive validation of their value hypothesis.

- What it didn't mean: It absolutely did not mean the product was good. They had clearly, undeniably failed the usability hypothesis.

Suddenly, the decision was obvious. They didn't need to pivot away from the core problem—far from it. They needed to persevere, but with a brand new learning goal laser-focused on one thing: streamlining the user experience in the next sprint.

The Pivot, Persevere, or Park Framework

Your decision-making framework should be just that straightforward. This isn't a time for endless debate. It's a time for a clear-eyed assessment of the evidence you've gathered against your original hypothesis.

Your MVP's results are not a grade. They are a signpost. Your job is to read it correctly and choose the next path, even if it’s not the one you expected.

Let’s be honest about the incentives at play. They almost always push teams to persevere, no matter what the data says. The sunk cost fallacy is a powerful drug, and everyone wants to show forward progress. In their book Designing Your Life, Stanford's Bill Burnett and Dave Evans talk about the danger of getting attached to a single outcome. The agile MVP process is a system designed specifically to fight that very human bias.

It gives you official permission to be wrong.

So here’s the grounded, actionable takeaway: before your post-MVP debrief meeting, force the team to make a choice. Frame the entire discussion around these three, and only these three, options:

- Persevere: The core hypothesis held up. We're doubling down to solve the next most important problem, whether that's scale, usability, or retention.

- Pivot: The core hypothesis was shot down, but in the process, we stumbled upon a new, more promising opportunity. We're going to repurpose what we've built to test this new direction.

- Park: The hypothesis was invalidated, and no clear pivot emerged from the wreckage. We're stopping all work on this initiative, documenting what we learned, and moving on.

Making this choice deliberately—and with conviction—is what separates products that win from projects that just meander until they run out of road.

Common Questions About MVP Agile Development

Even the most disciplined teams hit a wall when theory meets reality. The clean lines of an MVP process get messy fast. Let's tackle the common friction points that pop up when the rubber actually meets the road.

How Do You Handle Scope Creep From Stakeholders?

Your strongest defense is that single, core question you defined at the very start. Every single new feature request has to be measured against that one learning goal.

When someone proposes a new idea, the conversation isn't, "Can we build this?" It's, "How does this specific feature help us answer our core question?"

If it doesn't directly contribute, it’s not scope creep.

It's a distraction.

This completely reframes the discussion. You aren’t just saying no; you're protecting the integrity of the entire experiment. A great practice is to log these ideas in a separate "Iteration 2" or "Parking Lot" backlog. This turns a hard "no" into a strategic "not now," which keeps stakeholders happy and your MVP ruthlessly focused.

What Is the Difference Between an MVP and a Prototype?

This distinction is absolutely critical. A prototype answers questions about usability and feasibility: Can users figure this out? Can we actually build it?

An MVP, on the other hand, answers questions about value and viability: Will users even use this? And will they pay for it?

Think of it like this: a prototype is often a non-functional model you show people in a controlled setting to de-risk a design. An MVP is a functional, albeit minimal, product you release into the wild to see what people actually do, not what they say they'll do. You prototype to de-risk a single screen; you use an MVP to de-risk the entire business model.

Can You Run an MVP Process Without a Dedicated Engineering Team?

Absolutely. An MVP's primary purpose is to maximize learning, not code.

A "no-code" MVP built with tools like Zapier, Airtable, and a simple landing page builder can be incredibly effective for validating demand. Another powerful, code-free option is a concierge MVP, where you manually perform the service for your first few users.

The medium doesn't matter nearly as much as the integrity of the learning loop: build, measure, learn. The "build" part can literally be a spreadsheet and an email. The key is getting something out there that generates real user data. To see how this works in practice, these insightful minimum viable product examples break down how other companies did it.

Answering these questions isn't just about managing a project; it's about building a learning engine. Figr helps you accelerate that engine by turning your product context into production-ready designs, flows, and test cases, so your team can focus on the learning, not the labor. Ship UX faster with Figr.