Most PMs use AI like a vending machine.

Insert prompt. Receive output. The faster the output, the better. Five screens in thirty seconds. Impressive, right?

Here's what's actually happening: the thinking happens before you type. The AI is just a production tool. You're outsourcing execution while keeping all the hard cognitive work to yourself.

The best PMs use AI differently. They use it to surface what they haven't considered. To explore before they execute. To think through problems more thoroughly than they could alone.

Robbin Schuurman, a product management trainer who works with hundreds of PMs, put it bluntly: "Generative AI is a reflection tool. It reflects the quality of your thinking."

The difference in output quality is dramatic. But the difference in learning is even more important.

The Vending Machine Trap

"Build me a checkout flow."

The AI generates a checkout flow. Five screens. Cart, shipping, payment, confirmation, success. It looks reasonable. You move forward.

But should you move forward yet?

Tom Leung, a 20-year PM veteran, ran an experiment testing five AI tools on the same PRD task. His conclusion after 45 minutes of hands-on testing: "Some PMs use AI because they don't want to think deeply about the product. They're looking for AI to do the hard work of strategy, prioritization, and trade-off analysis. This never works."

The vending machine approach skips these questions: Does it handle your edge cases? Does it fit your product's existing patterns? Does it consider scenarios you haven't thought about?

These questions aren't optional. They're the difference between shipping something that works and shipping something that fails in production.

I used this approach for months before realizing what I was missing. The outputs looked fine. The features shipped. But I kept encountering the same edge cases, the same user confusions, the same "why didn't we think of that?" moments after launch.

Why Your First Idea Is Rarely Your Best Idea

Your first idea isn't your best idea. It's your most available idea. The one closest to the surface. The one most similar to what you've seen before.

This is why divergent exploration matters. Before converging on a solution, you need to generate multiple possible approaches. Not one. Three, five, seven. Each solving the problem differently.

Research from IDEO on design thinking found that teams who spend more time in the problem space consistently produce more innovative solutions than teams who rush to solutions. As Linus Pauling put it, "To have a good idea you must first have lots of ideas." The investment in exploration pays dividends in outcome quality.

But most AI tools work against this. They're optimized for speed of generation, not quality of thinking. They give you what you asked for instead of helping you figure out what you should ask for.

The tool won't diverge unless you tell it to. Left to its own defaults, it will converge on the most likely solution and generate that.

The Exploration Approach

PMs who shared their AI workflows in Lenny Rachitsky's newsletter use prompts that look nothing like "build me a checkout flow."

Their favorite prompts when thinking about a feature or go-to-market strategy:

- "What am I missing here?"

- "What am I being overly optimistic about?"

- "What is a macro event that could totally reverse the outcomes of this?"

Another PM in the same thread uses AI to remove personal bias and understand edge cases:

- "Tell me 5 reasons this feature won't work as intended"

- "Tell me 5 unintended consequences of this feature"

See the pattern? These prompts don't ask for outputs. They ask for inputs. For considerations. For the thinking that should happen before any screen gets generated.

One PM summarized it perfectly: "Incredibly helpful for steelmanning the other side of an argument when drafting a proposal."

This is exploration. This is using AI to extend your thinking, not replace it.

What Exploration Actually Looks Like

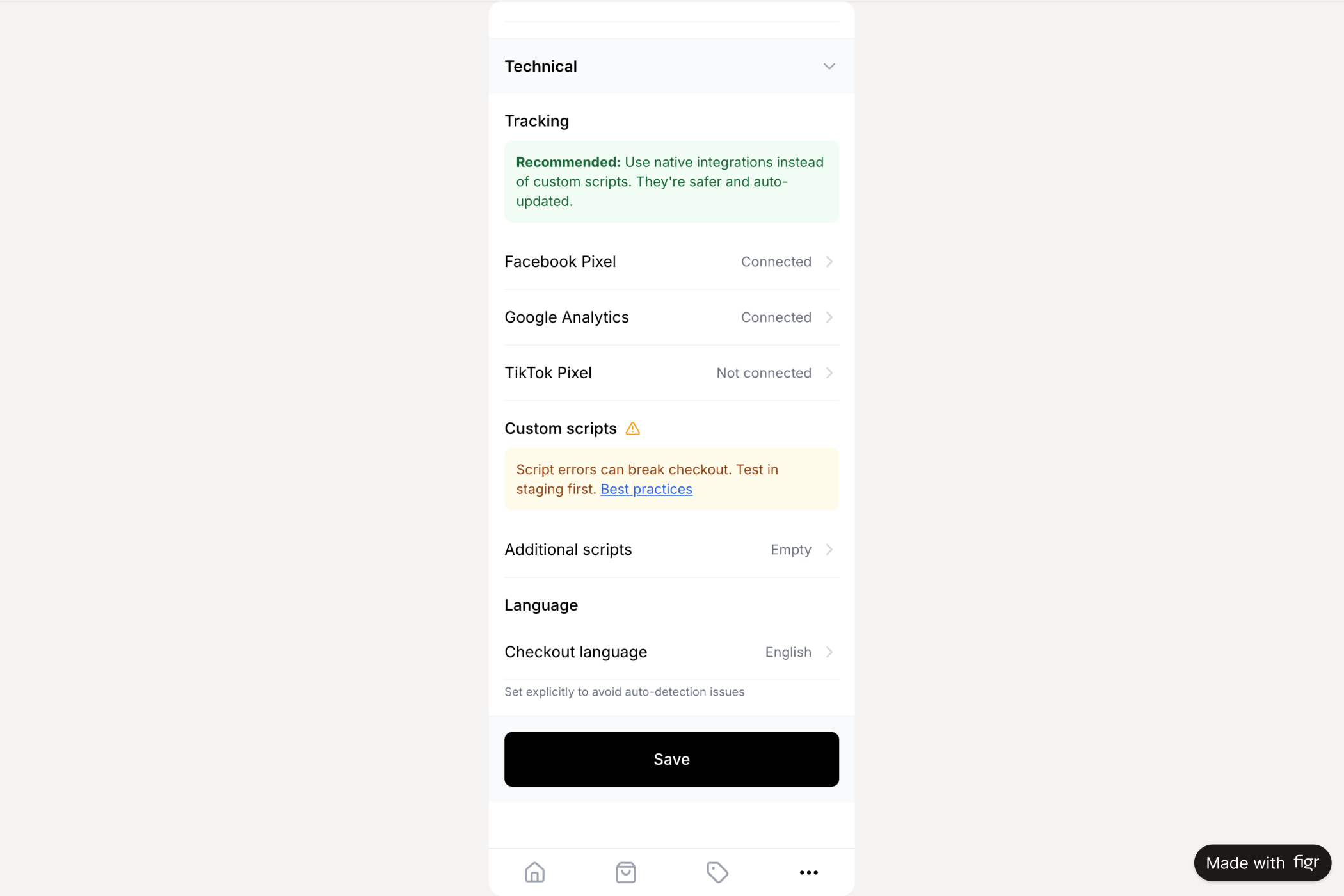

"I need to design a checkout flow for our e-commerce product. Before generating anything, help me think through: What edge cases should I consider? How do our competitors handle this? What patterns work for high-value purchases versus quick buys?"

This prompt invites exploration. The AI surfaces considerations you might have missed: empty cart handling, out-of-stock during checkout, payment failures with retry logic, address validation errors, partial shipments for multi-item orders.

You learn something before you generate anything. The final output is better because your understanding is better.

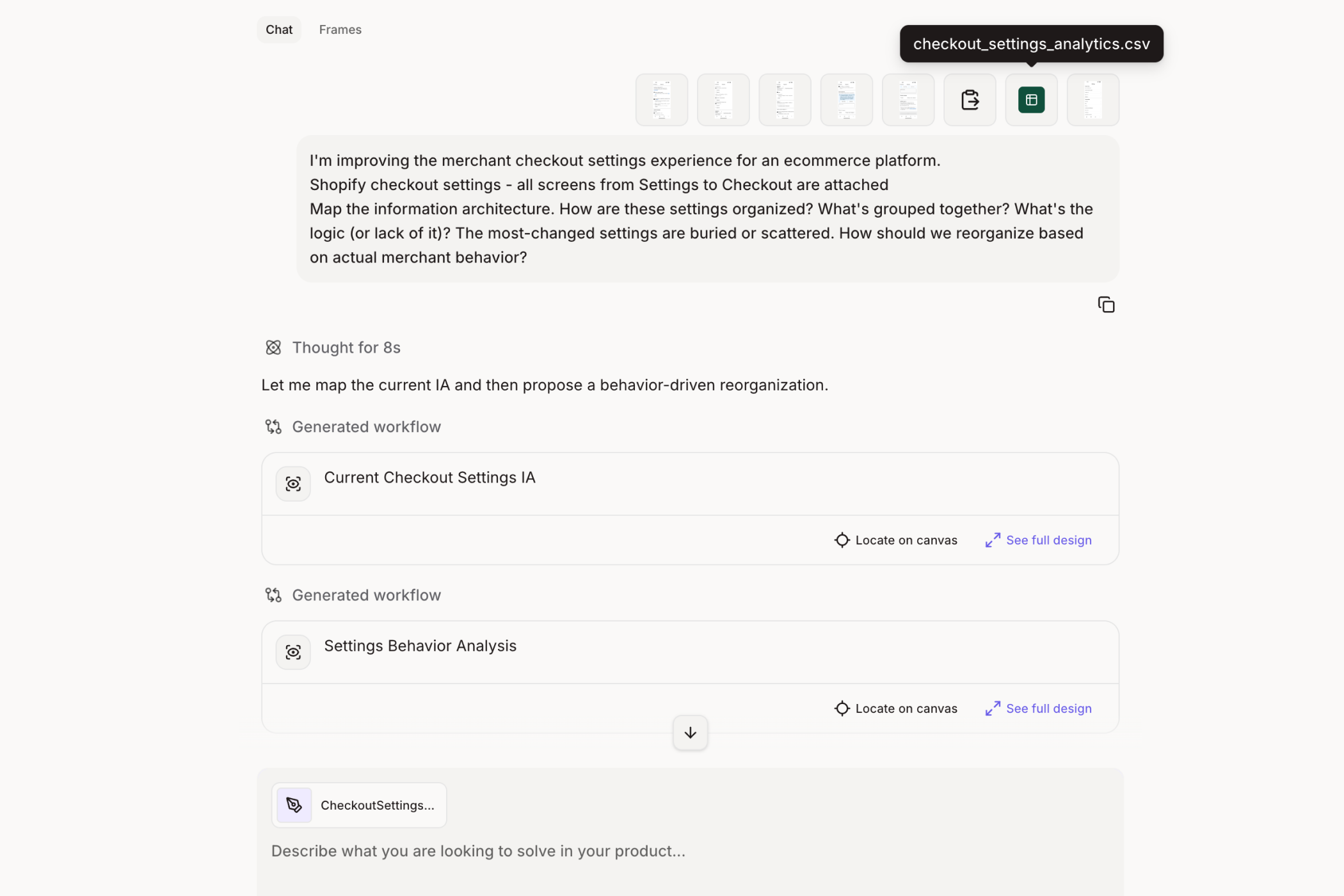

The Shopify checkout project on Figr used this approach. Before generating screens, the tool explored: What are the common drop-off points in checkout flows? What happens when items go out of stock mid-checkout? How should we handle partial shipments?

The result wasn't just better screens. It was better thinking.

The Shopify checkout project used this approach. Before generating screens, Figr explored: What are the common drop-off points in checkout flows? What happens when items go out of stock mid-checkout? How should we handle partial shipments?

→ See the Shopify checkout flow, designed after thorough problem exploration

Three Exploration Patterns That Work

Pattern 1: Edge Case Surfacing

"What could go wrong with this feature? What states have I not considered?"

This is the pattern most PMs skip entirely. You're building a file upload feature. You think about the happy path: user selects file, file uploads, success message appears.

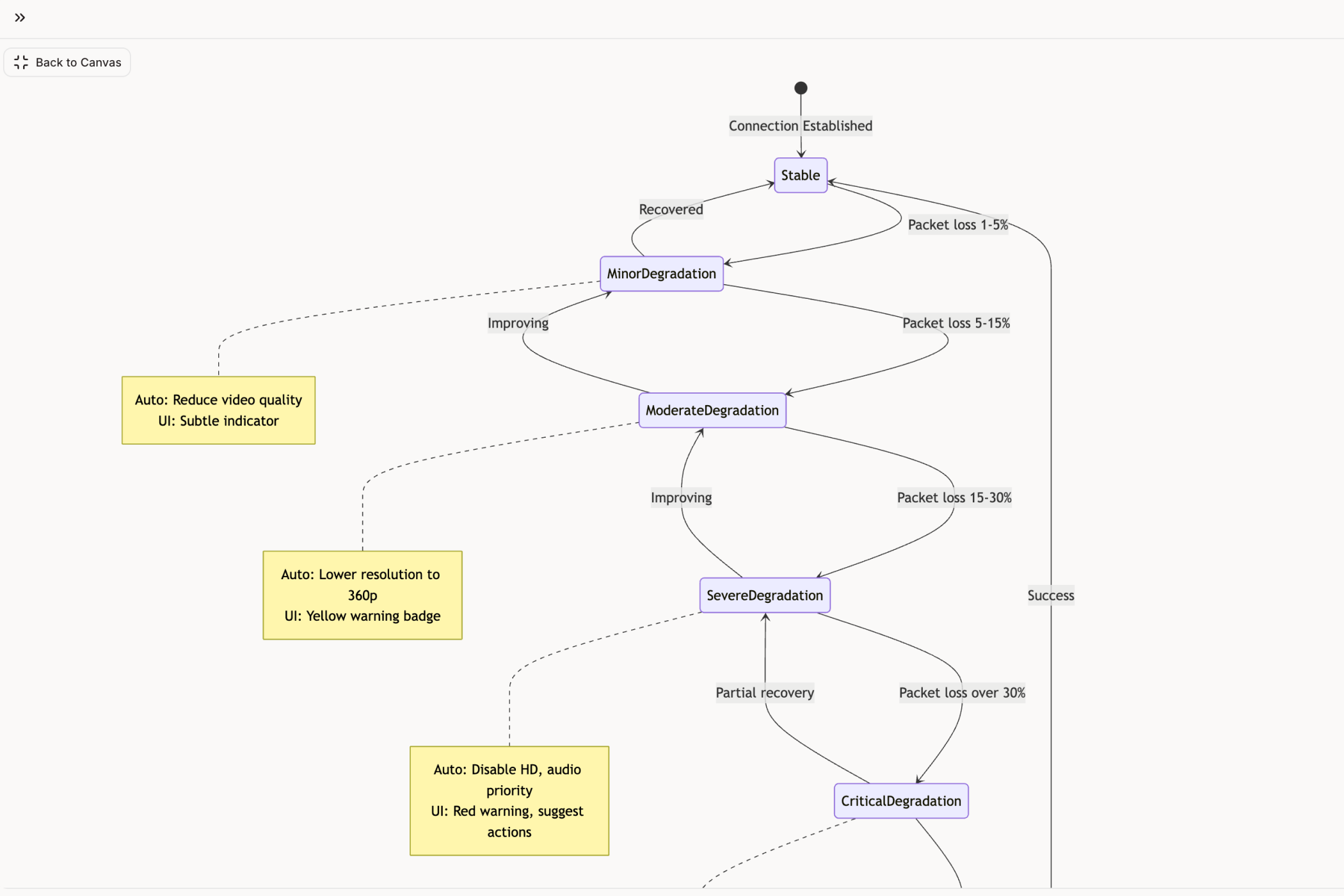

But file uploads have at least 14 states, not 1. Network drops. Size limits. Duplicate conflicts. Permission errors. Timeout handling. Progress indicators. Partial uploads. Resume capability.

Tools trained on large UI datasets know what file uploads need. They know what network degradation looks like, as a spectrum, not binary. This pattern knowledge surfaces what your individual experience might miss.

The Zoom network degradation project mapped every scenario: packet loss, bandwidth throttling, reconnection loops. Each state documented. Each UX decision explained.

Pattern 2: The Pre-Mortem

Gary Klein popularized the pre-mortem technique: Imagine the project has already failed. Now explain why.

This flips the typical planning process. Instead of asking "how do we succeed?", you ask "what killed us?"

Klein's research found that pre-mortems reduce overconfidence, force teams to confront failure head-on, and foster more realistic planning. The technique works because it breaks the cycle of self-reinforcing optimism that blinds us to potential risks.

Use this prompt pattern with AI:

"It's six months from now. This feature has failed completely. What went wrong? Be specific."

The answers surface risks you wouldn't have considered. Political blockers. Technical debt. Market timing. User adoption friction.

Shreyas Doshi, who led product at Stripe, Twitter, and Google, teaches a related framework: "Think like a box, explore every perspective of the problem before jumping to solutions."

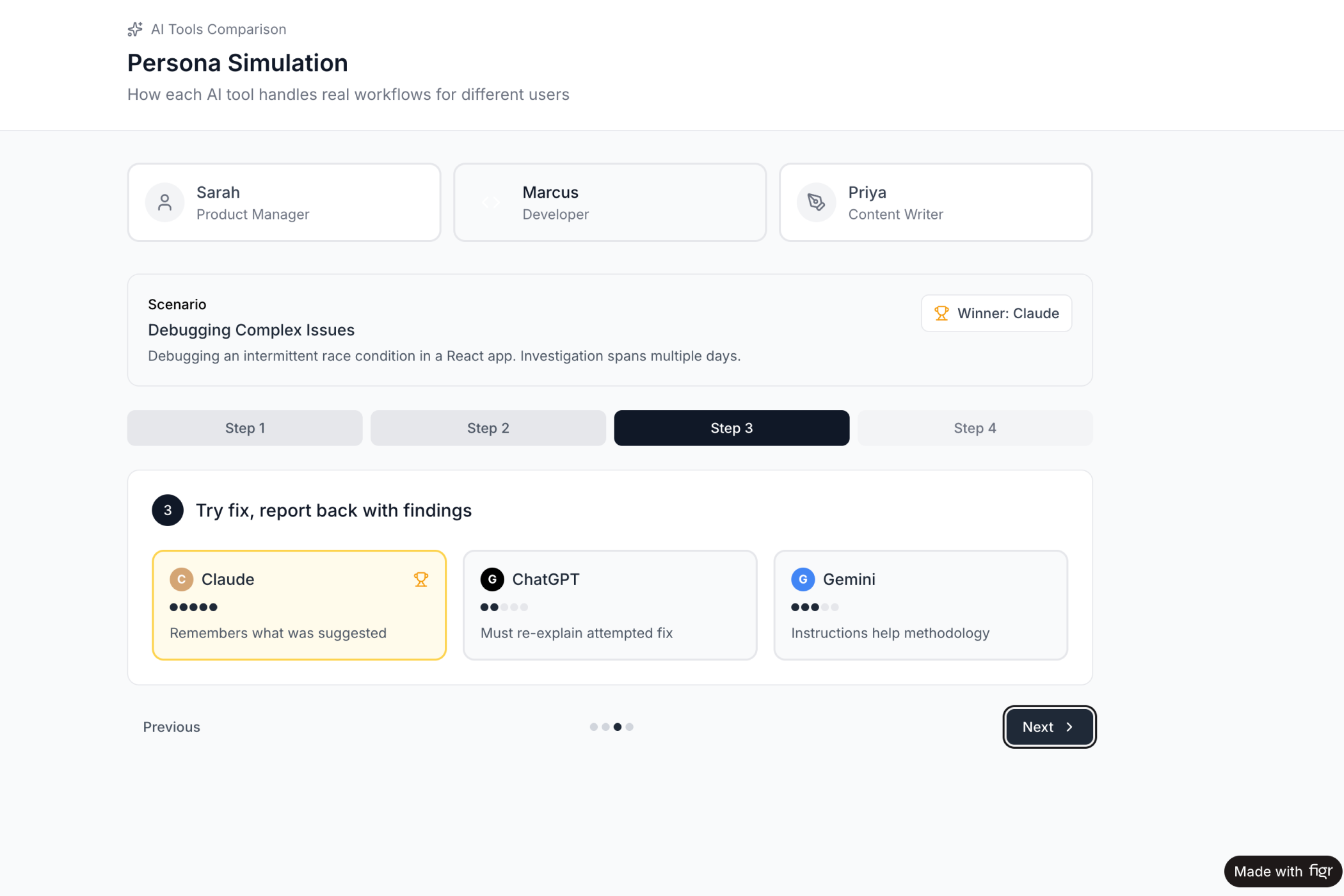

Pattern 3: Persona Simulation

"How would a power user experience this? A newcomer? Someone with accessibility needs?"

Different users reveal different friction points.

The Gemini vs Claude vs ChatGPT comparison simulated three personas interacting with each product: a PM doing research, a developer debugging, a writer drafting. Each persona exposed different strengths and weaknesses.

The result wasn't just a comparison chart. It was insight into what each tool actually does well, and why.

→ See the persona simulation across three AI products

The Four Questions to Ask Before Any Screen

Before generating any screen, the best PMs ask four questions. These questions prevent premature commitment and ensure you're building the right thing.

Question One: What is the user trying to accomplish?

Not what feature are you building. What job is the user hiring this feature to do?

The performance review dashboard example failed because the PM focused on the feature, not the job. Users didn't want a dashboard. They wanted to complete reviews quickly and fairly.

Question Two: What's preventing them from accomplishing it today?

The obstacle matters. If the obstacle is lack of information, maybe you need a dashboard. If the obstacle is decision fatigue, maybe you need guided steps. If the obstacle is too many clicks, maybe you need automation.

Question Three: What happens if we get this wrong?

Not every feature carries equal risk. A checkout flow affects revenue directly. A profile page affects it indirectly. The risk level should influence how much exploration you do.

Question Four: What do I believe that might not be true?

This is the hardest question. Some PMs use AI specifically to identify assumptions in their hypotheses. They feed their product thinking into AI and ask it to surface the assumptions behind their logic.

These questions don't take long. Five minutes, maybe ten. But they change what you generate. They turn "build me a dashboard" into "help me explore how users might complete performance reviews with less friction."

Why Writing Is Still Thinking

One PM in a deep dive on AI workflows made a confession: "I think by writing. So if I give away too much of the writing, I give away too much of the thinking too."

This captures something important. The act of writing isn't separate from the act of thinking. Writing forces clarity. Writing exposes gaps. Writing is how half-formed ideas become real.

When you outsource writing entirely to AI, you outsource thinking. The output might look polished, but it lacks the depth that comes from wrestling with the material yourself.

The best approach isn't to avoid AI. It's to use AI to explore, then write your own synthesis. Use AI to generate options. Use AI to surface considerations. But write the final version yourself.

That's where the learning happens.

The Difference Between Thinking and Typing

Here's the uncomfortable truth: your typing speed isn't your bottleneck. Your thinking is.

AI can type infinitely fast. It can generate screens, PRDs, user stories, and documentation at a rate no human can match.

But it can't think for you. It can't know your users. It can't understand your company's strategy. It can't navigate your organizational politics. It can't feel the frustration of a user who's been struggling with your product for months.

The PM who explores before generating produces better outputs. Not because AI is smarter when you ask nicely. Because the PM's own thinking improves through the exploration process.

You learn what edge cases exist. You understand competitor trade-offs. You consider perspectives you would have missed.

The exploration makes the generation better. And the exploration makes you better too.

In Short

AI is not just a generation tool. It's a thinking tool.

The best PMs use AI to surface what they don't know, not just to produce what they already imagined. They use prompts like "What am I missing?" and "Why might this fail?" They simulate personas. They run pre-mortems. They explore divergent options before converging.

This is harder than typing "build me a checkout flow." It takes more time upfront. It requires confronting uncertainty instead of rushing past it.

But it's the difference between shipping features and shipping the right features.

Ready to try exploration-first design? Figr is built for PMs who want to think through problems before generating solutions. Deep product memory. Edge case surfacing. UX pattern matching from 200,000+ screens. It's AI that thinks with you, not just for you.

→ Start exploring your next product development cycle

This article was written for PMs who want to do more than generate. It draws on research from Lenny Rachitsky's newsletter, Tom Leung's Fireside PM experiments, Shreyas Doshi's product frameworks, Gary Klein's pre-mortem research, and real workflows shared by PMs building products every day.