A hammer sees every problem as a nail. Most AI tools see every problem as a screen to generate.

You type a prompt. You get an interface. The interface looks plausible. But something is wrong. The tool skipped the thinking and jumped to the building. It produced an answer before you finished asking the question.

This is the tyranny of the obvious solution. AI tools optimized for speed produce outputs before you've had time to explore the problem space. They give you what you asked for instead of helping you figure out what you should ask for.

The best PMs have learned to resist this. They use AI differently. Not as a production line that spits out screens, but as a thinking partner that helps them understand before they build.

The Top-Down Trap

Most AI prototyping tools work top-down. You describe a solution. The tool generates it. Fast. Impressive. Done.

But here's what gets lost: the exploration that should happen before solution generation. The questions you should be asking. The alternatives you should be considering. The assumptions you should be testing.

A PM at an enterprise HR tech company told me about her most expensive mistake. She used an AI tool to generate a performance review dashboard. The tool produced a beautiful interface in minutes. She showed it to stakeholders. They loved it. Engineering built it. Users ignored it.

What went wrong? She skipped the problem phase. She knew users needed to complete performance reviews. She assumed they needed a dashboard to do it. She never asked whether a dashboard was the right solution or whether some other approach might work better.

The AI tool was perfectly capable of generating alternatives. But she never asked it to. And the tool never offered. It did exactly what she requested: build a dashboard. The fact that a dashboard was the wrong answer wasn't the tool's fault. But the tool's speed and confidence made it easier to skip the questioning phase entirely.

This is what I call the Top-Down Trap. When generation is instant, exploration feels like a waste of time. Why consider alternatives when you can just build your first idea and see?

What Problem-First AI Looks Like

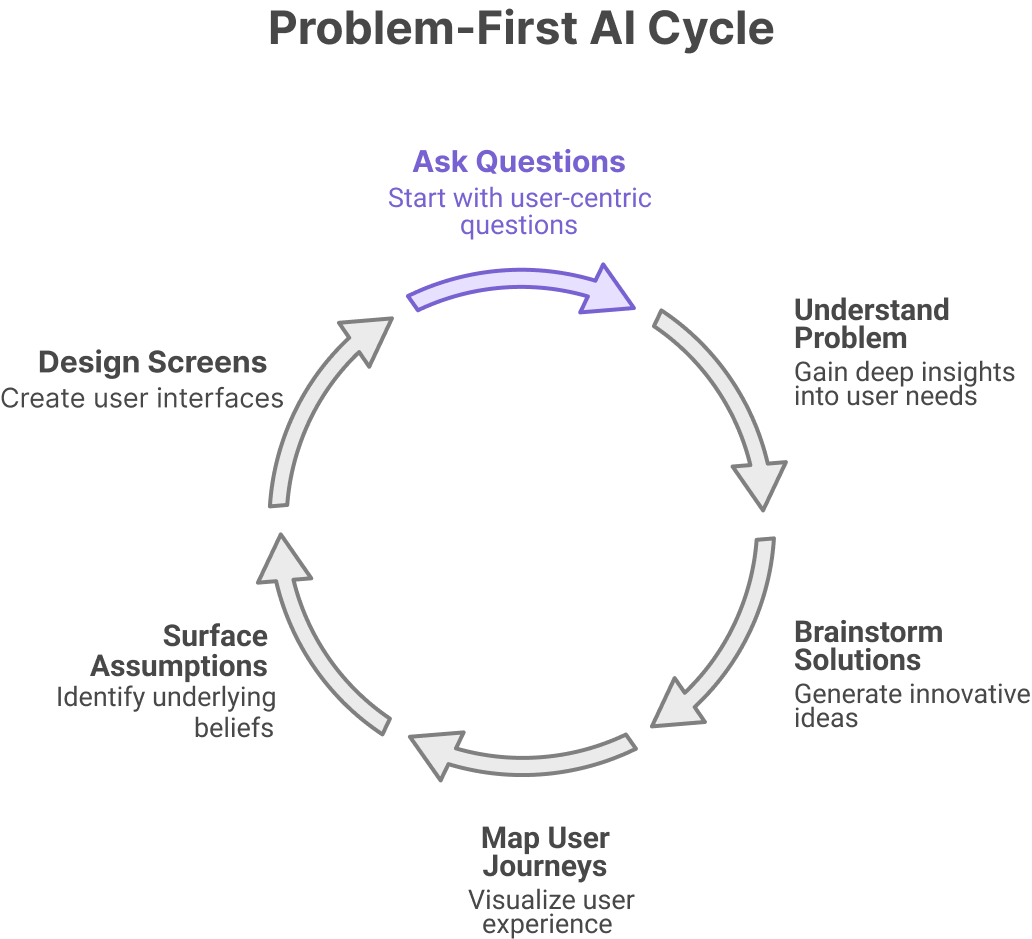

The alternative is problem-first thinking. Before you generate any screens, you generate understanding.

What does this look like in practice? It means starting with questions, not solutions. Who is the user? What job are they trying to do? What's blocking them? What does success look like? What have they tried before? Why did those attempts fail?

The basic gist is this: you should understand the problem so well that the solution becomes obvious, rather than generating solutions to discover what the problem might be.

Problem-first AI tools support this sequence. They help you brainstorm before you wireframe. They help you map user journeys before you design screens. They help you surface assumptions before you commit to approaches.

Think of it like the difference between a GPS that only gives directions and a GPS that first asks where you actually want to go. The second one is slower to start but far more likely to get you somewhere useful.

Research from IDEO on design thinking found that teams who spend more time in the problem space consistently produce more innovative solutions than teams who rush to solutions. The investment in exploration pays dividends in outcome quality.

The Exploration Phase Most PMs Skip

Here's a phase that most PMs skip entirely: divergent exploration.

Divergent exploration means generating multiple possible approaches before converging on one. Not one solution. Three, five, seven. Each solving the problem differently.

Why does this matter? Because your first idea is rarely your best idea. It's your most available idea. The one closest to the surface. The one most similar to what you've seen before.

Divergent exploration surfaces alternatives. Maybe the performance review problem is best solved with a dashboard. Or maybe it's best solved with a wizard. Or a chatbot. Or a mobile-first flow. Or a notification system. Each approach has tradeoffs. You can't evaluate tradeoffs you never generated.

How do you get AI to help with divergent exploration? You ask explicitly. "Generate five different approaches to solving this problem." "What are three alternative ways to handle this user flow?" "Show me how different products have approached similar challenges."

The tool won't diverge unless you tell it to. Left to its own defaults, it will converge on the most likely solution and generate that. Your job is to resist convergence until you've explored the space

The Four Questions Before Any Screen

Before generating any screen, the best PMs ask four questions. These questions prevent premature commitment and ensure you're building the right thing.

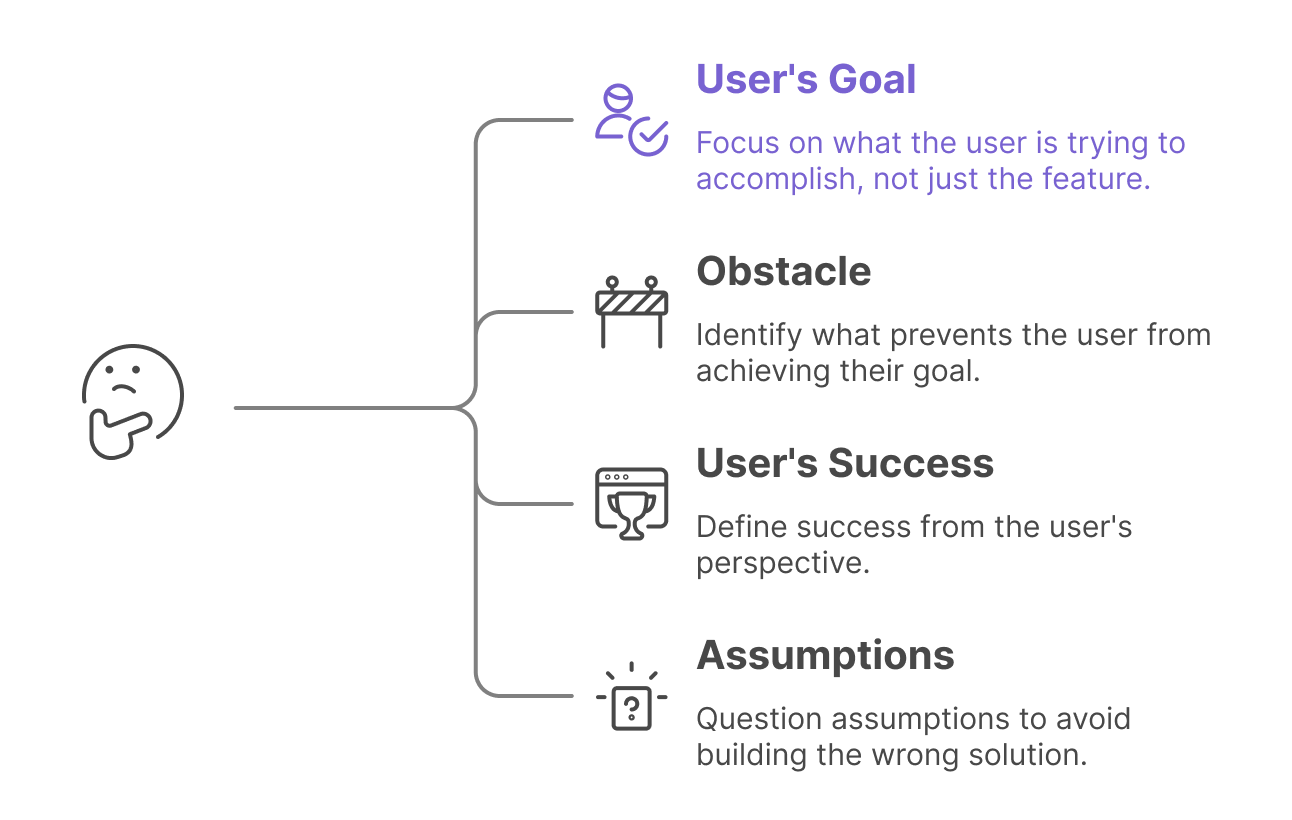

Question One: What is the user trying to accomplish?

Not what feature are you building. What job is the user hiring this feature to do? The performance review dashboard example failed because the PM focused on the feature, not the job. Users didn't want a dashboard. They wanted to complete reviews quickly and fairly.

Question Two: What's preventing them from accomplishing it today?

The obstacle matters. If the obstacle is lack of information, maybe you need a dashboard. If the obstacle is decision fatigue, maybe you need guided steps. If the obstacle is time, maybe you need automation. The solution should match the obstacle.

Question Three: What would success look like from the user's perspective?

Not from your perspective. Not from the business's perspective. From the user's perspective. How would they describe the ideal outcome in their own words?

Question Four: What assumptions am I making that might be wrong?

Every solution embeds assumptions. A dashboard assumes users want to self-serve data. A wizard assumes users need guidance. What are your assumptions? How would you know if they were wrong?

These questions don't take long. Five minutes, maybe ten. But they change what you generate. They turn "build me a dashboard" into "help me explore how users might complete performance reviews with less friction."

The Exploration Phase Most PMs Skip

Here's a phase that most PMs skip entirely: divergent exploration.

Divergent exploration means generating multiple possible approaches before converging on one. Not one solution. Three, five, seven. Each solving the problem differently.

Why does this matter? Because your first idea is rarely your best idea. It's your most available idea. The one closest to the surface. The one most similar to what you've seen before.

Divergent exploration surfaces alternatives. Maybe the performance review problem is best solved with a dashboard. Or maybe it's best solved with a wizard. Or a chatbot. Or a mobile-first flow. Or a notification system. Each approach has tradeoffs. You can't evaluate tradeoffs you never generated.

How do you get AI to help with divergent exploration? You ask explicitly. "Generate five different approaches to solving this problem." "What are three alternative ways to handle this user flow?" "Show me how different products have approached similar challenges."

The tool won't diverge unless you tell it to. Left to its own defaults, it will converge on the most likely solution and generate that. Your job is to resist convergence until you've explored the space.

[FIGR INTEGRATION PLACEHOLDER]

Topic: "The bottom-up design philosophy that explores before building"

Capability highlighted: "Figr's brainstorm → wireframe → design → prototype workflow that mirrors how human designers think"

Suggested visual: "Comparison diagram: Left shows 'Top-Down AI' (prompt → finished screen, single path). Right shows 'Bottom-Up AI' (problem framing → multiple concepts → selected direction → refined prototype, branching paths)."

Copy direction: Figr was built on a different philosophy. Instead of jumping to finished screens, Figr supports exploration first. Start with brainstorming to surface the problem space. Generate multiple wireframe directions before committing. Only then add fidelity and interaction. This bottom-up approach mirrors how experienced designers actually think. They explore before they commit. The result is solutions that solve the right problem, not just solutions that look good.

The Four Questions Before Any Screen

Before generating any screen, the best PMs ask four questions. These questions prevent premature commitment and ensure you're building the right thing.

Question One: What is the user trying to accomplish?

Not what feature are you building. What job is the user hiring this feature to do? The performance review dashboard example failed because the PM focused on the feature, not the job. Users didn't want a dashboard. They wanted to complete reviews quickly and fairly.

Question Two: What's preventing them from accomplishing it today?

The obstacle matters. If the obstacle is lack of information, maybe you need a dashboard. If the obstacle is decision fatigue, maybe you need guided steps. If the obstacle is time, maybe you need automation. The solution should match the obstacle.

Question Three: What would success look like from the user's perspective?

Not from your perspective. Not from the business's perspective. From the user's perspective. How would they describe the ideal outcome in their own words?

Question Four: What assumptions am I making that might be wrong?

Every solution embeds assumptions. A dashboard assumes users want to self-serve data. A wizard assumes users need guidance. What are your assumptions? How would you know if they were wrong?

These questions don't take long. Five minutes, maybe ten. But they change what you generate. They turn "build me a dashboard" into "help me explore how users might complete performance reviews with less friction."

From Thinking Partner to Production Tool

The shift is mental, not technical. The same AI tool can be a thinking partner or a production machine. The difference is how you use it.

When you use AI as a production tool, you come with answers. "Build me a settings page." The AI executes. You evaluate. If the execution is good, you're done. If not, you iterate on execution details.

When you use AI as a thinking partner, you come with questions. "What are the different ways users might configure this feature?" The AI explores. You learn. You refine your understanding. Only then do you move to execution.

In short, the best PMs use AI to think better, not just build faster.

This doesn't mean slowing down. It means front-loading the thinking so the building goes smoothly. A PM who spends thirty minutes exploring the problem space and then generates one prototype often ships faster than a PM who generates five prototypes without exploration, because the first PM builds the right thing the first time.

The Economic Case for Exploration

Why do PMs skip exploration? Because it feels like overhead. The prototype is the deliverable. Time spent not-prototyping feels like time wasted.

But consider the economics. A prototype that solves the wrong problem costs far more than the time spent exploring alternatives. It costs stakeholder review time. Design revision time. Engineering time. Opportunity cost of the features you didn't build instead.

Marty Cagan, in "Inspired," argues that the biggest risk in product development is not building the thing wrong but building the wrong thing. Exploration is how you mitigate that risk. It's not overhead. It's insurance.

The math is straightforward. If thirty minutes of exploration saves you from building the wrong feature, you've saved weeks of downstream work. If it doesn't, you've lost thirty minutes. The expected value of exploration is almost always positive.

The Monday Morning Shift

This week, before you generate any screens, try pausing at the problem phase.

Take your next feature idea and write down the four questions. What is the user trying to accomplish? What's preventing them? What would success look like? What assumptions might be wrong?

Then ask your AI tool to generate three different approaches to solving the problem. Not three variations of the same approach. Three genuinely different approaches. Evaluate them against your answers to the four questions.

Only then pick a direction and build.

Notice how the exploration changes your output. Notice how alternatives surface tradeoffs you wouldn't have considered. Notice how the final prototype feels more grounded because you understand why you chose it over the alternatives.

The hammer doesn't get to decide what the problem is. Neither should your AI tool. That's your job. Use the tool to think, not just to build. The quality of what you ship depends on the quality of the questions you ask before you start generating.